It is a bright summer day in the Bavarian Alps, and I am looking up at a castle that doesn’t quite belong to reality. The towers rise like frozen music, white against the blue sky, as if someone sketched them in a fairy-tale book and forgot to erase the pencil lines.

On 12 July 2025, it became clear this was more than simply good scenery. UNESCO placed Neuschwanstein—along with Linderhof, Herrenchiemsee, and the mountain lodge at Schachen—on the World Heritage List. The title is long, official, and somewhat stiff. The buildings themselves are anything but. The decision comes just weeks before the 180th anniversary of King Ludwig II’s birthday, which will be celebrated on 25 August.

A King in Retreat

King Ludwig II of Bavaria came to power in 1864, young, idealistic, and some whispered eccentric. Politics in Munich bored him. The newly unified Germany, dominated by Prussia, left little space for a romantic Bavarian monarch.

So he escaped. Not to another country, but into stone, stucco, and gilded mirrors. Ludwig II personally approved every design detail, from swan motifs to mosaic tiles. Architects despaired at his endless changes.

The castles were not meant for court life. They were built for him alone: dreamscapes inspired by medieval legends, Wagner’s operas, and the shimmering Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.

The Four Castles

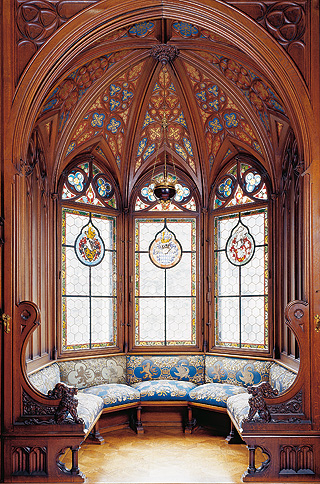

Neuschwanstein: perched above the village of Hohenschwangau, its towers shaped by medieval fantasy. Ludwig lived here for only 172 days, but in that time, he managed to fill it with swan motifs, painted legends, and views that seem borrowed from a stage set. Neuschwanstein means New Swan Stone, a nod to Wagner’s Swan Knight opera.

Linderhof: smaller, more intimate, Rococo in style. Here, Ludwig had a grotto built just to stage his favorite operas—complete with artificial lake and electric lighting (this in the 1870s!).

Herrenchiemsee: on an island in Lake Chiemsee, a tribute to France’s Louis XIV. The central block stands completed; the rest exists only in Ludwig’s sketches.

Schachen: a wooden chalet high in the mountains, with an upstairs hall dressed like an Ottoman palace—because why not? You can only reach Schachen by hiking 10 km uphill. Ludwig had champagne brought in on a mule-back

Along the Romantic Road

Driving the Romantische Straße, I find that Ludwig’s world leaks into the landscape. Medieval towns, timber-framed houses, onion-domed churches—it’s a slow-motion postcard.

Neuschwanstein is not officially on the route, but it feels like the journey’s crown. You pass vineyards and wheat fields, then suddenly the Alps break the horizon, and there it is: a white silhouette, dreamlike, impossible.

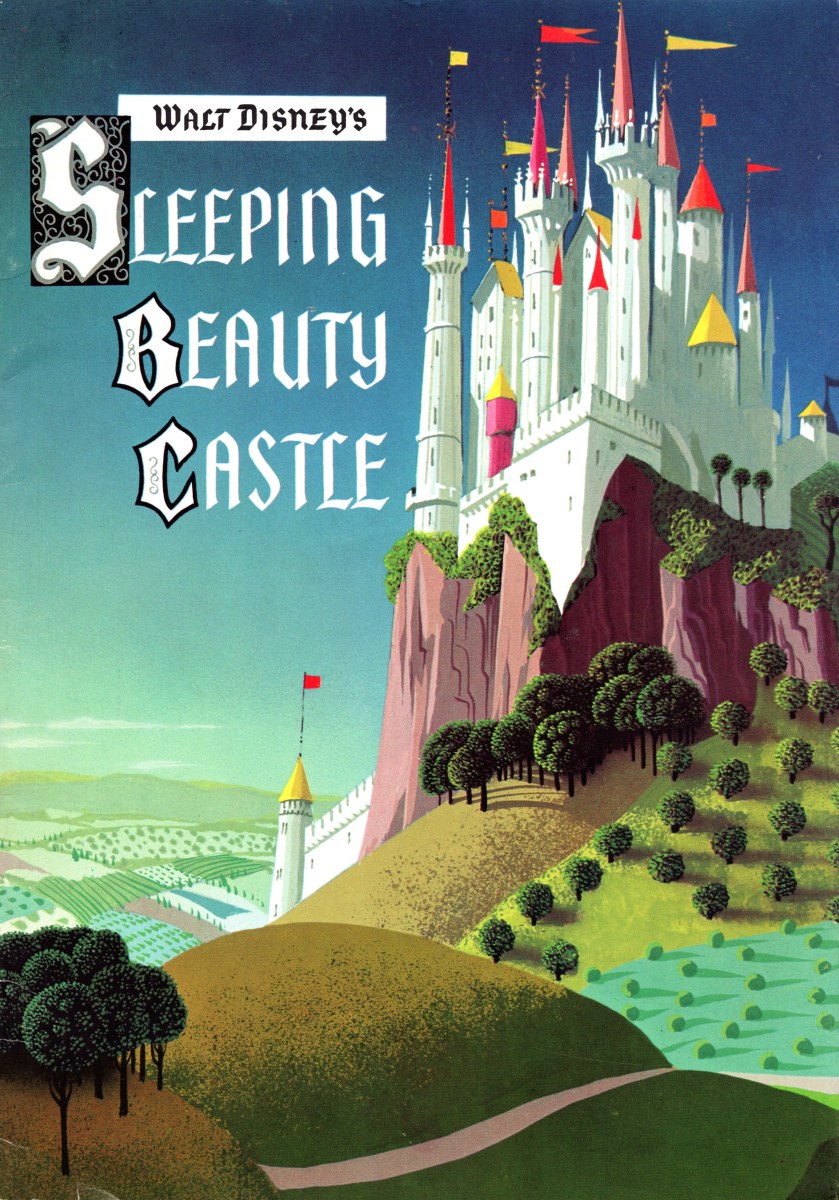

And here’s the twist: Walt Disney may never have set foot inside Neuschwanstein, but the castle’s silhouette still travelled across the Atlantic. In California, it re-emerged as Sleeping Beauty’s Castle, a place where fairy tales feel real for millions of children (and quite a few grown-ups). Every child who has ever walked through Disneyland’s gates has unknowingly stepped into Ludwig’s dream.

Beyond Bavaria

The Bavarian kings were not confined to their own borders. The House of Wittelsbach once ruled lands that touched Austria and reached into parts of Switzerland. Ludwig himself had a peculiar affection for the Swiss founding site, the Rütli meadow, and even tried to buy it for yet another castle. The Swiss, politely but firmly, declined.

A Legacy Sealed

UNESCO’s recognition in 2025 feels like the final act in Ludwig’s opera. He died mysteriously in 1886, his castles incomplete, his debts towering. And yet—walking through their corridors today—you feel his presence more strongly than in any portrait.

They are not just buildings. They are Bavaria dreaming. And somehow, they make you dream too.